Counting

Although you may have thought you had a pretty good grasp on the notion of counting at the age of three, it turns out that you had to wait until now to learn how to really count. Aren’t you glad you took this class now?! But seriously, counting is like the foundation of a house (where the house is all the great things we will do later in this book, such as machine learning). Houses are awesome. Foundations, on the other hand, are pretty much just concrete in a hole. But don’t make a house without a foundation. It won’t turn out well.

Counting with Steps

Definition: Step Rule of Counting (aka Product Rule of Counting)

If an experiment has two parts, where the first part can result in one of $m$ outcomes and the second part can result in one of $n$ outcomes regardless of the outcome of the first part, then the total number of outcomes for the experiment is $m \cdot n$.

Rewritten using set notation, the Step Rule of Counting states that if an experiment with two parts has an outcome from set $A$ in the first part, where $|A| = m$, and an outcome from set $B$ in the second part (where the number of outcomes in $B$ is the same regardless of the outcome of the first part), where $|B| = n$, then the total number of outcomes of the experiment is $|A||B| = m \cdot n $.

Simple Example: Consider a hash table with 100 buckets. Two arbitrary strings are independently hashed and added to the table. How many possible ways are there for the strings to be stored in the table? Each string can be hashed to one of 100 buckets. Since the results of hashing the first string do not impact the hash of the second, there are 100 * 100 = 10,000 ways that the two strings may be stored in the hash table.

Peter Norvig, the author of the canonical textbook "Artificial Intelligence" made the following compelling point on why computer scientists need to know how to count. To start, let's set a baseline for a really big number: The number of atoms in the observable universe, often estimated to be around 10 to the 80th power ($10^{80}$). There certainly are a lot of atoms in the universe. As a leading expert said,

“Space is big. Really big. You just won’t believe how vastly, hugely, mind-bogglingly big it is. I mean, you may think it’s a long way down the road to the chemist, but that’s just peanuts to space.” - Douglas Adams

This number is often used to demonstrate tasks that computers will never be able to solve. Problems can quickly grow to an absurd size, and we can understand why using the Step Rule of Counting.

There is an art project to display every possible picture. Surely that would take a long time, because there must be many possible pictures. But how many? We will assume the color model known as True Color, in which each pixel can be one of $2^{24}$ ≈ 17 million distinct colors.

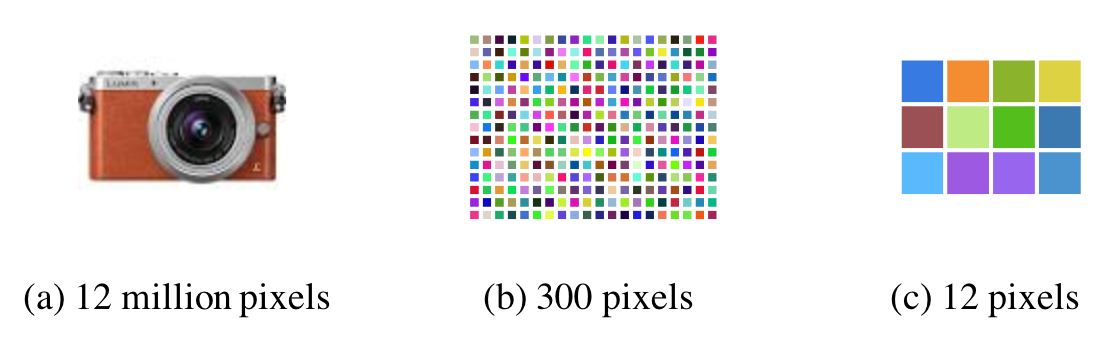

How many distinct pictures can you generate from (a) a smartphone camera shown with 12 million pixels, (b) a grid with 300 pixels, and (c) a grid with just 12 pixels?

Answer: We can use the step rule of counting. An image can be created one pixel at a time, step by step. Each time we choose a pixel you can select its color out of 17 million choices. An array of $n$ pixels produces (17 million)$^n$ different pictures. (17 million)$^{12}$ ≈ $10^{86}$, so the tiny 12-pixel grid produces a million times more pictures than the number of atoms in the universe! How about the 300 pixel array? It can produce $10^{2167}$ pictures. You may think the number of atoms in the universe is big, but that’s just peanuts to the number of pictures in a 300-pixel array. And 12M pixels? $10^{86696638}$ pictures.

Example: Unique states of Go

For example, a Go board has 19 × 19 points where a user can place a stone. Each of the points can be empty or occupied by black or white stone. By the Step Rule of Counting, we can compute the number of unique board configurations.

In Go there are 19x19 points. Each point can have a black stone, white stone, or no stone at all.

Here we are going to construct the board one point at a time, step by step. Each time we add a point we have a unique choice where we can decide to make the point one of three options: {Black, White, No Stone}. Using this construction we can apply the Step Rule of Counting. If there was only one point, there would be three unique board configurations. If there were four points you would have $3 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 \cdot 3 = 81$ unique combinations. In Go there are $3^{(19×19)} ≈ 10^{172}$ possible board positions. The way we constructed our board didn't take into account which ones were illegal by the rules of Go. It turns out that "only" about $10^{170}$ of those positions are legal. That is about the square of the number of atoms in the universe. In other words: if there was another universe of atoms for every single atom, only then would there be as many atoms in the universe as there are unique configurations of a Go board.

As a computer scientist this sort of result can be very important. While computers are powerful, an algorithm which needed to store each configuration of the board would not be a reasonable approach. No computer can store more information than atoms in the universe squared!

The above argument might leave you feeling like some problems are incredibly hard as a result of the product rule of counting. Let’s take a moment to talk about how the product rule of counting can help! Most logarithmic time algorithms leverage this principle.

Imagine you are building a machine learning system that needs to learn from data and you want to synthetically generate 10 million unique data points for it. How many steps would you need to encode to get to 10 million? Assuming that at each step you have a binary choice, the number of unique data points you produce will be $2^n$ by the Step Rule of counting. If we chose $n$ such that $\log_{2} 10,000,000 < n$. You would only need to encode $n=24$ binary decisions.

Example: Rolling two dice. Two 6-sided dice, with faces numbered 1 through 6, are rolled. How many possible outcomes of the roll are there?

Solution: Note that we are not concerned with the total value of the two die ("die" is the singular form of "dice"), but rather the set of all explicit outcomes of the rolls. Since the first die can come up with 6 possible values and the second die similarly can have 6 possible values (regardless of what appeared on the first die), the total number of potential outcomes is 36 (= 6 × 6). These possible outcomes are explicitly listed below as a series of pairs, denoting the values rolled on the pair of dice:

Counting with or

If you want to consider the total number of unique outcomes, when outcomes can come from source $A$ or source $B$, then the equation you use depends on whether or not there are outcomes which are both in $A$ and $B$. If not, you can use the simpler "Mutually Exclusive Counting" rule. Otherwise you need to use the slightly more involved Inclusion Exclusion rule.

Definition: Mutually Exclusive Counting

If the outcome of an experiment can either be drawn from set $A$ or set $B$, where none of the outcomes in set $A$ are the same as any of the outcomes in set $B$ (called mutual exclusion), then there are $|A \or B| = |A|+|B|$ possible outcomes of the experiment.

Example: Sum of Routes. A route finding algorithm needs to find routes from Nairobi to Dar Es Salaam. It finds routes that either pass through Mt Kilimanjaro or Mombasa. There are 20 routes that pass through Mt Kilimanjaro, 15 routes that pass through Mombasa and 0 routes which pass through both Mt Kilimanjaro and Mombasa. How many routes are there total?

Solution: Routes can come from either Mt Kilimanjaro or Mombasa. The two sets of routes are mutually exclusive as there are zero routes which are in both groups. As such the total number of routes is addition: 20 + 15 = 35.

If you can show that two groups are mutually exclusive counting becomes simple addition. Of course not all sets are mutually exclusive. In the example above, imagine there had been a single route which went through both Mt Kilimanjaro and Mombasa. We would have double counted that route because it would be included in both the sets. If sets are not mutually exclusive, counting the or is still addition, we simply need to take into account any double counting.

Definition: Inclusion-Exclusion Counting

If the outcome of an experiment can either be drawn from set $A$ or set $B$, and sets $A$ and $B$ may potentially overlap (i.e., it is not the case that $A$ and $B$ are mutually exclusive), then the number of outcomes of the experiment is $|A \or B| = |A|+|B| −|A \and B|$.

Note that the Inclusion-Exclusion Principle generalizes the Sum Rule of Counting for arbitrary sets $A$ and $B$. In the case where $A \and B = ∅$, the Inclusion-Exclusion Principle gives the same result as the Sum Rule of Counting since $|A \and B| = 0$.

Example: An 8-bit string (one byte) is sent over a network. The valid set of strings recognized by the receiver must either start with "01" or end with "10". How many such strings are there?

Solution: The potential bit strings that match the receiver’s criteria can either be the 64 strings that start with "01" (since that last 6 bits are left unspecified, allowing for $2^6 = 64$ possibilities) or the 64 strings that end with "10" (since the first 6 bits are unspecified). Of course, these two sets overlap, since strings that start with "01" and end with "10" are in both sets. There are $2^4$ = 16 such strings (since the middle 4 bits can be arbitrary). Casting this description into corresponding set notation, we have: $|A|$ = 64, $|B|$ = 64, and $|A \and B|$ = 16, so by the Inclusion-Exclusion Principle, there are 64 + 64 − 16 = 112 strings that match the specified receiver’s criteria.

Overcounting and Correcting

One strategy for counting is sometimes to overcount a solution and then correct for any duplicates. This is especially common when it is easier to generate all outcomes under some relaxed assumptions, or someone introduces contraints. If you can argue that you have over-counted each element the same multiple number of times, you can simply correct by using division. If you can count exactly how many elements were over-counted you can correct using subtraction.

As a simple example to demonstrate the point, lets revisit the problem of generating all images, but this time lets just have 4 pixels (2x2) and each pixel can only be blue or white. How many unique images are there? Generating any image is a four step process where you choose each pixel one at a time. Since each pixel has two choices there are $2^4 = 16$ unique images (they are not exactly Picasso — but hey, it's 4 pixels):

Now lets say we add in a new "constraint" that we only want to accept pictures which have an odd number of pixels turned blue. There are two ways of getting to the answer. You could start out with the original 16 and work out that you need to subtract off 8 images that have either 0, 2 or 4 blue pixels (which is easier to work out after the next chapter). Or you could have counted up using Mutually Exclusive Counting: there are 4 ways of making an image with 1 pixel and 4 ways of making an image with 3. Both approaches lead to the same answer, 8.

Next lets add a much harder constraint: mirror indistinction. If you can flip any image horizontally to create another, they are no longer considered unique. For example these two both show up in our set of 8 odd-blue pixel images, but they are now considered to be the same (they are indistinct after a horizontal flip):

How many images have an odd number of pixels taking into account mirror indistinction? The answer is that for each unique image with odd numbers of blue pixels, under this new constraint, you have counted it twice: itself and its horizonal flip. To convince yourself that each image has been counted exactly twice you can look at all of the examples in the set of 8 images with an odd number of blue pixels. Each image is next to one which is indistinct after a horizontal flip. Since each image was counted exactly twice in the set of 8, we can divide by two to get the updated count. If we list them out we can confirm that there are 8/2=4 images left after this last constraint:

Applying any math (counting included) to novel contexts can be as much an art as it is a science. In the next chapter we will build a useful toolset from the basic first principles of counting by steps, and counting by "or".