Independence

So far we have talked about mutual exclusion as an important "property" that two or more events can have. In this chapter we will introduce you to a second property: independence. Independence is perhaps one of the most important properties to consider! Like for mutual exclusion, if you can establish that this property applies (either by logic, or by declaring it as an assumption) it will make analytic probability calculations much easier!

Definition: Independence

Two events are said to be independent if knowing the outcome of one event does not change your belief about whether or not the other event will occur. For example, you might say that two separate dice rolls are independent of one another: the outcome of the first dice gives you no information about the outcome of the second -- and vice versa.

$$ \p(E | F) = \p(E) $$Alternative Definition

Another definition of independence can be derived by using an equation called the chain rule, which we will learn about later, in the context where two events are independent. Consider two indepedent events $A$ and $B$: \begin{align*} \P(A,B) &= \p(A) \cdot \p(B|A) && \href{ ../../part1/prob_and/}{\text{Chain Rule}} \\ &= \p(A) \cdot \p(B) && \text{Independence} \end{align*}

Independence is Symmetric

This definition is symmetric. If $E$ is independent of $F$, then $F$ is independent of $E$. We can prove that $\p(F | E) = \p(F)$ implies $\p(E | F) = \p(E)$ starting with a law called Bayes' Theorem which we will cover shortly: \begin{align*} \p(E | F) &= \frac{\p(F|E) \cdot \p(E)}{\p(F)} && \text{Bayes Theorem} \\ &= \frac{\p(F) \cdot \p(E)}{\p(F)} && \p(F | E) = \p(F) \\ &= \p(E) && \text{Cancel} \end{align*}

Generalized Independence

Events $E_1 , E_2 , \dots , E_n$ are independent if for every subset with $r$ elements (where $r \leq n$): $$ \p(E_{1'}, E_{2'}, \dots, E_{r'}) = \prod_{i=1}^r \p(E_i') $$

As an example, consider the probability of getting 5 heads on 5 coin flips where we assume that each coin flip is independent of one another.

How to Establish Independence

How can you show that two or more events are independent? The default option is to show it mathematically. If you can show that $\p(E | F) = \p(E)$ then you have proven that the two events are independent. When working with probabilities that come from data, very few things will exactly match the mathematical definition of independence. That can happen for two reasons: first, events that are calculated from data or simulation are not perfectly precise and it can be impossible to know if a discrepancy between $\p(E)$ and $\p(E |F)$ is due to inaccuracy in estimating probabilities, or dependence of events. Second, in our complex world many things actually influence each other, even if just a tiny amount. Despite that we often make the wrong, but useful, independence assumption. Since independence makes it so much easier for humans and machines to calculate composite probabilities, you may declare the events to be independent. It could mean your resulting calculation is slightly incorrect — but this "modelling assumption" might make it feasible to come up with a result.

Independence is a property which is often "assumed" if you think it is reasonable that one event is unlikely to influence your belief that the other will occur (or if the influence is negligible). Let's work through an example to better understand.

Example: Parallel Networks

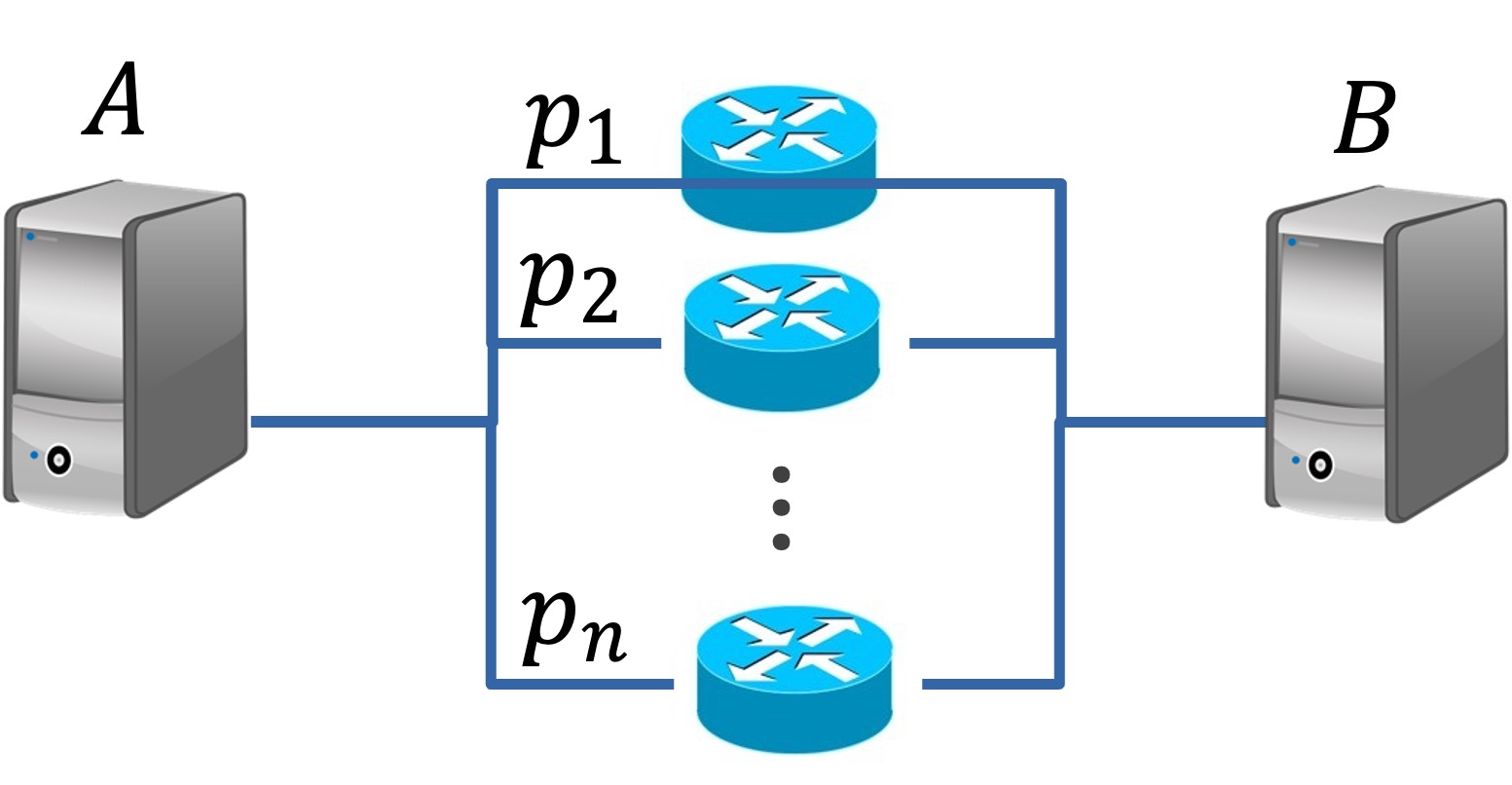

Over networks, such as the internet, computers can send information. Often there are multiple paths (mediated by routers) between two computers and as long as one path is functional, information can be sent. Consider the following parallel network with $n$ independent routers, each with probability $p_i$ of functioning (where 1 ≤ $𝑖$ ≤ $𝑛$). Let $E$ be the event that there is a functional path from $A$ to $B$. What is $\p(E)$?

A simple network that connects two computers, A and B.

Independence and Compliments

Given independent events $A$ and $B$, we can prove that $A$ and $B^C$ are independent. Formally we want to show that: $\P( A B^C) = \P( A)\P(B^C)$. This starts with a rule called the Law of Total Probability which we will cover shortly. \begin{align*} \P (AB^C ) &= \P (A) - \P (AB) && \href{ ../../part1/law_total/}{\text{LOTP}} \\ &= \P (A) - \P (A)\P (B) &&\text{Independence}\\ &= \P (A)[1 - \P (B)]&&\text{Algebra}\\ &= \P (A)\P(B^C)&&\href{ ../..//part1/probability/}{\text{Identity 1}}\\ \end{align*}

Conditional Independence

We saw earlier that the laws of probability still held if you consistently conditioned on an event. As such, the definition of independence also transfers to the universe of conditioned events. We use the terminology "conditional independence" to refer to events that are independent when consistently conditioned. For example if someone claims that events $E_1, E_2, E_3$ are conditionally independent given event $F$. This implies that $$ \p(E_1, E_2, E_3 | F) = P(E_1|F) \cdot P(E_2|F) \cdot P(E_3|F) $$ Which can be written more succinctly in product notation $$ \p(E_1, E_2, E_3 | F) = \prod_{i=1}^3 P(E_i|F) $$